Pandemic 1918 and 2020 – Then and Now

Interestingly you can compare the Pandemics of 1918 and 2020? Recently a reporter asked Anastacia Palaszczuk, Premier of Queensland about the current pandemic. How did it compare to the one at the end of the First World War? In reply she said “That was then and this is now”. In other words, she indicated that the one hundred year difference meant the pandemics could not really be compared. Indeed one can see her point. For the reason that in 1918 there was not instant communication of news and forewarnings of what was happening. In addition there was not widespread commercial air travel allowing viruses to spread very quickly. Nor were thousands of people on cruise ships. Unfortunately, these have proven to be places where Covid 19 can spread easily. Moreover, countries did not have nation-wide health systems in place. In addition, medical knowledge is now more advanced.

Pandemic 1918 and 2020 – some similarities between then and now.

However, there are similarities. Unfortunately, then as now the Federal Government of Australia and the States did not present a unified front.

The Personal Human Cost

However one thing is for sure and certain, the personal toll on individual families cannot be overstated.

To emphasise this below are two descriptions of the impact on two families in the 1918 to 1920 pandemic.

Ottaway Family New South Wales

As an illustration is a headstone in Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery. This shows how the First World War and its aftermath caused grief to the Ottaway Family.

Sadly, the grave contains the remains of 19-year-old Harriet Ann Ottaway, who died on 2 July 1919. Also, the headstone has the name of her brother Henry James Ottaway. Tragically for the family, he died of wounds in Belgium, 23rd Sept 1917, aged 21 years.

Notably, Henry died at the infamous Battle of Passchendaele.

Unfortunately, Harriet’s headstone makes no mention of her own fight with ‘Spanish flu’. This was one of the reasons, the University of Sydney undertook a project on the 100th anniversary of the 1918 pandemic. The purpose was to show just how many died in the pandemic – many more than in the First World War. While we remember the Anzacs, there is silence about the other victims of what was a greater war.

The 1918-20 Pandemic Centenary

You can read the whole article by clicking on the link above. Below is an extract about Harriet Ottoway.

Harriet Ottoway

Harriet’s story typifies the enduring public silence around the pneumonic influenza pandemic of 1918–19. Worldwide, it killed an estimated 50-100 million people. That is at least three times all of the deaths caused by the First World War.

After the disease came ashore in January 1919, about a third of all Australians were infected. The flu left nearly 15,000 dead in under a year. Those figures match the average annual death rate for the Australian Imperial Force throughout 1914–18.

Arguably, we could consider 1919 as another year of war, albeit against a new enemy. Indeed, the typical victims had similar profiles: fit, young adults aged 20-40. The major difference was that in 1919, women like Harriet formed a significant proportion of the casualties.

Harriet died after nursing her older married sister. The sister survived.

The Heaton family of Lancashire England

This is my family. I was brought up knowing that my grandfather had died of Spanish flu in 1918. However, I did not know much about it or him. More recently through Ancestry.com I have found out more. My grandfather John Heaton was 27 when the First World War started.

.

John Heaton did not join the army. He was in a “reserved occupation”. His occupation was Fitter and Turner. There were several large engineering firms in our home town – Preston Lancashire. His father worked in the same industry and they were very busy manufacturing equipment for the war effort. My other grandfather William did join the army and served with the Loyal North Lancs in France. He survived the war but his brother, Richard, a stretcher bearer did not.

My grandfather John had married Annie Eskrick in 1911. My father James was born in December 1914.

John and Annie’s second child Jessie was born on the 25th May 1918. Her father John died on the 5th July 1918. Exhausted by working long hours on war work, he was not fit enough to resist the infection. He was 31.

Annie was left with two young children so the impact on the three of them was enormous. Working three or four cleaning jobs she kept the family. She worked at Doctor’s surgeries and Solicitor’s offices. She started early morning before the offices opened and went again in the evening after their day’s work was done. There were many others like her.

Preston and the pandemic

In the book “Preston and the First World War”, we are told in an extract written on 11th November 1918:

“At this time an epidemic of “Flu” is raging in the town and our coffin maker could not have a holiday and was paid double for this,” and

“I knew people were dropping dead all over the place. You wondered who was going to be next,”

Pandemic of 1918 to 1920

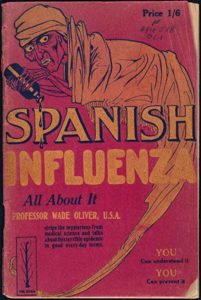

In fact, from 1918 to 1920 there was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic. This started in January 1918 and lasted until December 1920. It infected 500 million people which was then about one quarter of the World’s population. The lowest estimate of deaths was 17 million people. Some think it could have killed up to 50 million and maybe up to 100 million. This was at least three times all the deaths caused by the First World War.

Unsurprisingly, the official response to the epidemic was to censor the reports in Germany, United Kingdom, France and the United States. At all costs they wanted to avoid panic. The pandemic was known as the Spanish Flu but it did not originate in Spain. It is thought it started in the US and American troops brought it with them to the Western Front. The soldiers took the disease to their home countries.

Pandemic of 1918 and Australia

The disease did not reach Australia until 1919. The Australians named it “pneumonic flu”. It caused 12 000 – 15 000 deaths. Unfortunately it infected one third of all Australians. Although the mortality rate was much less than in other countries, it did severely affect the lives of many Australians. The death rate for aboriginal communities was around 50%. Mortality in Australia was smaller than in New Zealand and South Africa. In New Zealand the Maori population was particularly badly hit.

Pneumonic Flu of 1918 was very contagious

The Flu came in waves and was extremely virulent. Symptoms included shivering, headaches and back pain. There was acute muscle pain and vomiting, diarrhoea, watering eyes, running or bleeding nose, a sore throat and a dry cough.

This pandemic unlike the present one affected young people. Males in the 20-40 age group were the most prevalent.

Pandemic of 1918 and Government Action

Because Australia was then very remote from the world, the Australian authorities did have time to prepare. The Australian Quarantine Service monitored the pandemic. The result was that on October 17 1918, they implemented maritime quarantine. This was after there were outbreaks in South Africa and New Zealand. The first infected ship to enter Australian waters was the Mataram, from Singapore, which arrived in Darwin on 18 October 1918. Over the next six months the service intercepted 323 vessels, 174 of which carried the infection. Of the 81,510 people who were checked, 1102 were infected.

Second line of Defence

In 2018 to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the pandemic, a study was done about its impact on Australia. The National Museum of Australia reports: The federal government’s second line of defence was to establish a consistent response. The Federal and State authorities were to work together. It held a national influenza planning conference in Melbourne on 26–27 November 1918. State health ministers met with Commonwealth personnel.The conference agreed to the federal government taking responsibility for proclaiming which states were infected. They would also organise maritime and land quarantine. The states would arrange emergency hospitals, vaccination depots, ambulance services, medical staff and public awareness measures.

However, as now with Corona Virus the authorities began to work separately. The Federal Government and the States “were ultimately unable to provide a uniform response as the crisis worsened.”

States then as now closed their borders. The last time Queensland closed its border with New South Wales was in 1919. Henry Lawson ridiculed the rabbit-proof fence idea. The reason being, there is not much point trying to prevent border crossings when the disease is already on both sides of the border. Quarantine camps were set up on borders.

It was announced today March 26th 2020 that the Queensland Police were no longer trying to control the border between Coolangatta and Tweed Heads. As one man remarked, “My house is in Queensland, but my driveway is in New South Wales.”

Federal and State Responses 1919

The first case in Australia was in January 1919 in Melbourne. It was a very mild case and the Victorian authorities were unsure if it was the pneumonic flu. There was a delay in it being reported. The infection spread to New South Wales and South Australia. Tensions grew among the Federated States. Victoria was blamed for not alerting sooner. States made their own decisions about closing borders.

Dilemma then and now – Save Lives – Hurt the Economy

In 1919, Tasmania imposed a strict quarantine. Although the State had the lowest mortality rate in Australia , its economy suffered severely.

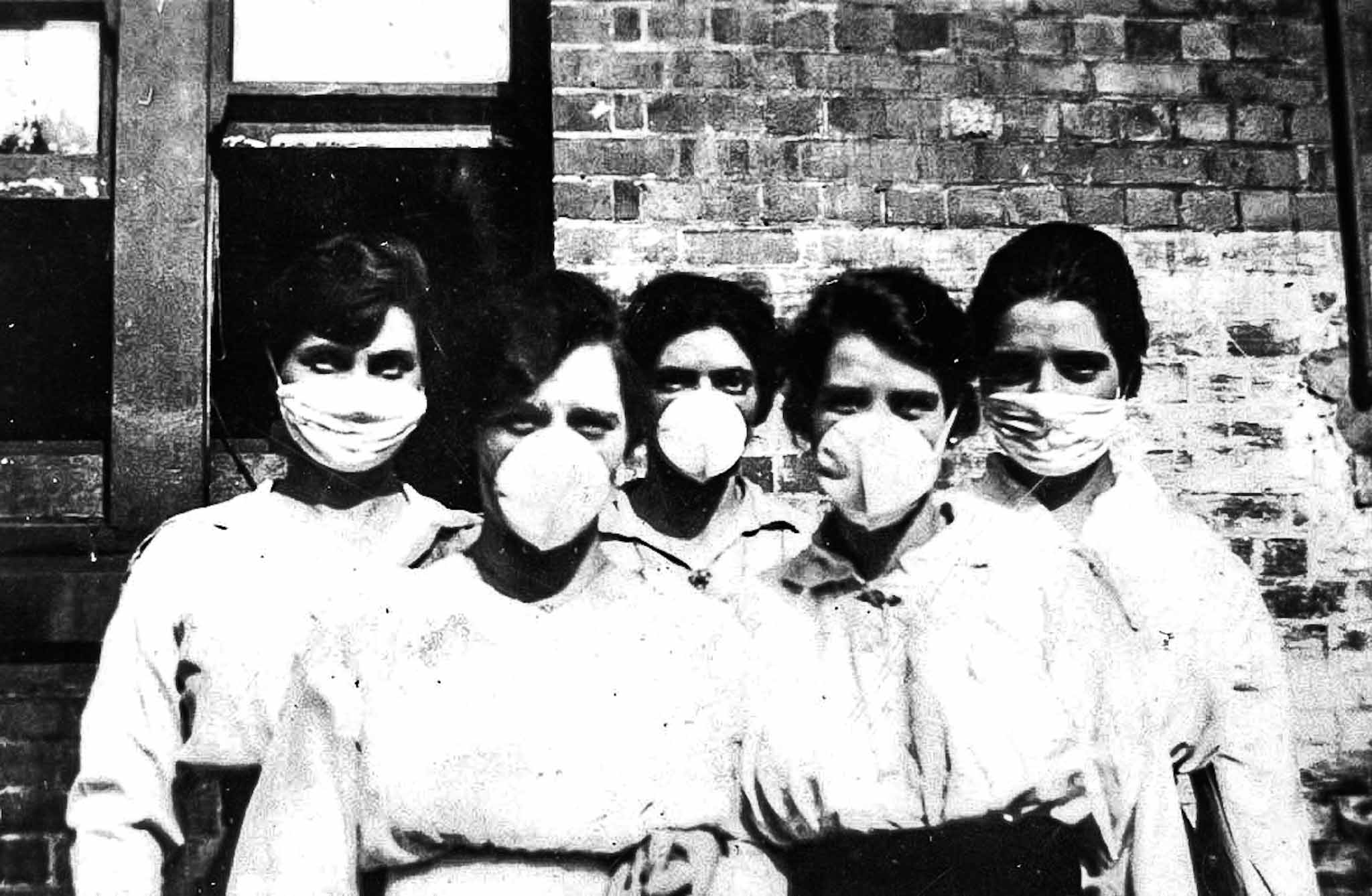

For a time it was compulsory to wear a mask in the street. Theatres, cinemas and dance halls closed, as did churches. The Sydney Easter Show was closed in 1919 as it has been in 2020.

In 2020

Initially, there was a united front. Encouragingly, a national cabinet of Federal and State leaders met and issued statements. The Federal Government wanted to keep schools open, Singapore and Hong Kong have kept their schools open. However various groups including independent schools and the Teachers Union did not agree. As a result, the states broke ranks and issued their own statements. In response came an article on the ABC website. Basically it said politicians were looking after their own interests. The states are responsible for education and health. If the leaders are to be elected again they do not want to be offside with the electorate, They do not want to be unpopular with the teaching unions, schools and the health professionals. The Federal Government is responsible for the economy. Keeping schools open would be better for the economy. In addition, the Prime Minister offered generous economic stimulus packages.

There’s a simple reason we get mixed messages from Morrison and the premiers

“In politics, it’s always important to remember who’s talking, and what skin they have in the game. And we’re seeing that in the confusing coronavirus messages,” writes Annabel Crabb. Read the full story

While self isolating, you may rely more on your computer. Possibly you may need help setting up streaming and remote access. We can help set up Netflix and Google Assistant. Call Cath.